The East India Company: The original corporate raiders

For a century, the East India Company conquered, subjugated and plundered vast tracts of south Asia. The lessons of its brutal reign have never been more relevant

The Mughal emperor Shah Alam hands a scroll to Robert Clive, the governor of Bengal, which transferred tax collecting rights in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa to the East India Company. Illustration: Benjamin West (1738–1820)/British Library

William Dalrymple

Wednesday 4 March 2015 05.59 GMTLast modified on Friday 10 April 201512.31 BST

One of the very first Indian words to enter the English language was the Hindustani slang for plunder: “loot”. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, this word was rarely heard outside the plains of north India until the late 18th century, when it suddenly became a common term across Britain. To understand how and why it took root and flourished in so distant a landscape, one need only visit Powis Castle.

The last hereditary Welsh prince, Owain Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn, built Powis castle as a craggy fort in the 13th century; the estate was his reward for abandoning Wales to the rule of the English monarchy. But its most spectacular treasures date from a much later period of English conquest and appropriation: Powis is simply awash with loot from India, room after room of imperial plunder, extracted by the East India Company in the 18th century.

There are more Mughal artefacts stacked in this private house in the Welsh countryside than are on display at any one place in India – even the National Museum in Delhi. The riches include hookahs of burnished gold inlaid with empurpled ebony; superbly inscribed spinels and jewelled daggers; gleaming rubies the colour of pigeon’s blood and scatterings of lizard-green emeralds. There are talwars set with yellow topaz, ornaments of jade and ivory; silken hangings, statues of Hindu gods and coats of elephant armour.

The audio long read Listen to William Dalrymple's long read on The East India Company: The original corporate raiders - Podcast

The latest in our audio long reads examines how, for a century, the East India Company conquered, subjugated and plundered vast tracts of south Asia. The lessons of its brutal reign have never been more relevant.

Listen

Such is the dazzle of these treasures that, as a visitor last summer, I nearly missed the huge framed canvas that explains how they came to be here. The picture hangs in the shadows at the top of a dark, oak-panelled staircase. It is not a masterpiece, but it does repay close study.

An effete Indian prince, wearing cloth of gold, sits high on his throne under a silken canopy. On his left stand scimitar and spear carrying officers from his own army; to his right, a group of powdered and periwigged Georgian gentlemen. The prince is eagerly thrusting a scroll into the hands of a statesmanlike, slightly overweight Englishman in a red frock coat.

The painting shows a scene from August 1765, when the young Mughal emperor Shah Alam, exiled from Delhi and defeated by East India Company troops, was forced into what we would now call an act of involuntary privatisation.

The scroll is an order to dismiss his own Mughal revenue officials in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa, and replace them with a set of English traders appointed by Robert Clive – the new governor of Bengal – and the directors of the EIC, who the document describes as “the high and mighty, the noblest of exalted nobles, the chief of illustrious warriors, our faithful servants and sincere well-wishers, worthy of our royal favours, the English Company”.

The collecting of Mughal taxes was henceforth subcontracted to a powerful multinational corporation – whose revenue-collecting operations were protected by its own private army.

It was at this moment that the East India Company (EIC) ceased to be a conventional corporation, trading and silks and spices, and became something much more unusual.

Within a few years, 250 company clerks backed by the military force of 20,000 locally recruited Indian soldiers had become the effective rulers of Bengal. An international corporation was transforming itself into an aggressive colonial power.

Using its rapidly growing security force – its army had grown to 260,000 men by 1803 – it swiftly subdued and seized an entire subcontinent.

Astonishingly, this took less than half a century.

The first serious territorial conquests began in Bengal in 1756; 47 years later, the company’s reach extended as far north as the Mughal capital of Delhi, and almost all of India south of that city was by then effectively ruled from a boardroom in the City of London. “What honour is left to us?” asked a Mughal official named Narayan Singh, shortly after 1765, “when we have to take orders from a handful of traders who have not yet learned to wash their bottoms?”

It was not the British government that seized India, but a private company, run by an unstable sociopath

We still talk about the British conquering India, but that phrase disguises a more sinister reality. It was not the British government that seized India at the end of the 18th century, but a dangerously unregulated private company headquartered in one small office, five windows wide, in London, and managed in India by an unstable sociopath – Clive.

In many ways the EIC was a model of corporate efficiency: 100 years into its history, it had only 35 permanent employees in its head office.

Nevertheless, that skeleton staff executed a corporate coup unparalleled in history: the military conquest, subjugation and plunder of vast tracts of southern Asia.

It almost certainly remains the supreme act of corporate violence in world history. For all the power wielded today by the world’s largest corporations – whether ExxonMobil, Walmart or Google – they are tame beasts compared with the ravaging territorial appetites of the militarised East India Company.

Yet if history shows anything, it is that in the intimate dance between the power of the state and that of the corporation, while the latter can be regulated, it will use all the resources in its power to resist.

When it suited, the EIC made much of its legal separation from the government. It argued forcefully, and successfully, that the document signed by Shah Alam – known as the Diwani – was the legal property of the company, not the Crown, even though the government had spent a massive sum on naval and military operations protecting the EIC’s Indian acquisitions.

But the MPs who voted to uphold this legal distinction were not exactly neutral: nearly a quarter of them held company stock, which would have plummeted in value had the Crown taken over. For the same reason, the need to protect the company from foreign competition became a major aim of British foreign policy.

Robert Clive, was an unstable sociopath who led the fearsome East India Company to its conquest of the subcontinent. Photograph: Hulton Archive/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The transaction depicted in the painting was to have catastrophic consequences. As with all such corporations, then as now, the EIC was answerable only to its shareholders. With no stake in the just governance of the region, or its long-term wellbeing, the company’s rule quickly turned into the straightforward pillage of Bengal, and the rapid transfer westwards of its wealth.

Before long the province, already devastated by war, was struck down by the famine of 1769, then further ruined by high taxation. Company tax collectors were guilty of what today would be described as human rights violations.

A senior official of the old Mughal regime in Bengal wrote in his diaries: “Indians were tortured to disclose their treasure; cities, towns and villages ransacked; jaghires and provinces purloined: these were the ‘delights’ and ‘religions’ of the directors and their servants.”

Bengal’s wealth rapidly drained into Britain, while its prosperous weavers and artisans were coerced “like so many slaves” by their new masters, and its markets flooded with British products.

A proportion of the loot of Bengal went directly into Clive’s pocket. He returned to Britain with a personal fortune – then valued at £234,000 – that made him the richest self-made man in Europe.

After the Battle of Plassey in 1757, a victory that owed more to treachery, forged contracts, bankers and bribes than military prowess, he transferred to the EIC treasury no less than £2.5m seized from the defeated rulers of Bengal – in today’s currency, around £23m for Clive and £250m for the company.

No great sophistication was required. The entire contents of the Bengal treasury were simply loaded into 100 boats and punted down the Ganges from the Nawab of Bengal’s palace to Fort William, the company’s Calcutta headquarters. A portion of the proceeds was later spent rebuilding Powis.

The painting at Powis that shows the granting of the Diwani is suitably deceptive: the painter, Benjamin West, had never been to India. Even at the time, a reviewer noted that the mosque in the background bore a suspiciously strong resemblance “to our venerable dome of St Paul”.

In reality, there had been no grand public ceremony. The transfer took place privately, inside Clive’s tent, which had just been erected on the parade ground of the newly seized Mughal fort at Allahabad. As for Shah Alam’s silken throne, it was in fact Clive’s armchair, which for the occasion had been hoisted on to his dining room table and covered with a chintz bedspread.

Later, the British dignified the document by calling it the Treaty of Allahabad, though Clive had dictated the terms and a terrified Shah Alam had simply waved them through.

As the contemporary Mughal historian Sayyid Ghulam Husain Khan put it: “A business of such magnitude, as left neither pretence nor subterfuge, and which at any other time would have required the sending of wise ambassadors and able negotiators, as well as much parley and conference with the East India Company and the King of England, and much negotiation and contention with the ministers, was done and finished in less time than would usually have been taken up for the sale of a jack-ass, or a beast of burden, or a head of cattle.”

By the time the original painting was shown at the Royal Academy in 1795, however, no Englishman who had witnessed the scene was alive to point this out.

Clive, hounded by envious parliamentary colleagues and widely reviled for corruption, committed suicide in 1774 by slitting his own throat with a paper knife some months before the canvas was completed. He was buried in secret, on a frosty November night, in an unmarked vault in the Shropshire village of Morton Say.

Many years ago, workmen digging up the parquet floor came across Clive’s bones, and after some discussion it was decided to quietly put them to rest again where they lay. Here they remain, marked today by a small, discreet wall plaque inscribed: “PRIMUS IN INDIS.”

Today, as the company’s most articulate recent critic, Nick Robins, has pointed out, the site of the company’s headquarters in Leadenhall Street lies underneath Richard Rogers’s glass and metal Lloyd’s building.

Unlike Clive’s burial place, no blue plaque marks the site of what Macaulay called “the greatest corporation in the world”, and certainly the only one to equal the Mughals by seizing political power across wide swaths of south Asia.

But anyone seeking a monument to the company’s legacy need only look around. No contemporary corporation could duplicate its brutality, but many have attempted to match its success at bending state power to their own ends.

The people of Allahabad have also chosen to forget this episode in their history. The red sandstone Mughal fort where the treaty was extracted from Shah Alam – a much larger fort than those visited by tourists in Lahore, Agra or Delhi – is still a closed-off military zone and, when I visited it late last year, neither the guards at the gate nor their officers knew anything of the events that had taken place there; none of the sentries had even heard of the company whose cannons still dot the parade ground where Clive’s tent was erected.

Instead, all their conversation was focused firmly on the future, and the reception India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, had just received on his trip to America.

One of the guards proudly showed me the headlines in the local edition of the Times of India, announcing that Allahabad had been among the subjects discussed in the White House by Modi and President Obama.

The sentries were optimistic. India was finally coming back into its own, they said, “after 800 years of slavery”. The Mughals, the EIC and the Raj had all receded into memory and Allahabad was now going to be part of India’s resurrection. “Soon we will be a great country,” said one of the sentries, “and our Allahabad also will be a great city.”

At the height of the Victorian period there was a strong sense of embarrassment about the shady mercantile way the British had founded the Raj.

The Victorians thought the real stuff of history was the politics of the nation state. This, not the economics of corrupt corporations, they believed was the fundamental unit of analysis and the major driver of change in human affairs.

Moreover, they liked to think of the empire as a mission civilisatrice: a benign national transfer of knowledge, railways and the arts of civilisation from west to east, and there was a calculated and deliberate amnesia about the corporate looting that opened British rule in India.

A second picture, this one commissioned to hang in the House of Commons, shows how the official memory of this process was spun and subtly reworked. It hangs now in St Stephen’s Hall, the echoing reception area of parliament. I came across it by chance late this summer, while waiting there to see an MP.

The painting was part of a series of murals entitled the Building of Britain. It features what the hanging committee at the time regarded as the highlights and turning points of British history: King Alfred defeating the Danes in 877, the parliamentary union of England and Scotland in 1707, and so on.

The image in this series which deals with India does not, however, show the handing over of the Diwani but an earlier scene, where again a Mughal prince is sitting on a raised dais, under a canopy. Again, we are in a court setting, with bowing attendants on all sides and trumpets blowing, and again an Englishman is standing in front of the Mughal. But this time the balance of power is very different.

Sir Thomas Roe, the ambassador sent by James I to the Mughal court, is shown appearing before the Emperor Jahangir in 1614 – at a time when the Mughal empire was still at its richest and most powerful.

Jahangir inherited from his father Akbar one of the two wealthiest polities in the world, rivalled only by Ming China. His lands stretched through most of India, all of what is now Pakistan and Bangladesh, and most of Afghanistan. He ruled over five times the population commanded by the Ottomans – roughly 100 million people. His capitals were the megacities of their day.

In Milton’s Paradise Lost, the great Mughal cities of Jahangir’s India are shown to Adam as future marvels of divine design.

This was no understatement: Agra, with a population approaching 700,000, dwarfed all of the cities of Europe, while Lahore was larger than London, Paris, Lisbon, Madrid and Rome combined.

This was a time when India accounted for around a quarter of all global manufacturing.

In contrast, Britain then contributed less than 2% to global GDP, and the East India Company was so small that it was still operating from the home of its governor, Sir Thomas Smythe, with a permanent staff of only six. It did, however, already possess 30 tall ships and own its own dockyard at Deptford on the Thames.

An East India Company grandee. Photograph: Getty Images

Jahangir’s father Akbar had flirted with a project to civilise India’s European immigrants, whom he described as “an assemblage of savages”, but later dropped the plan as unworkable.

Jahangir, who had a taste for exotica and wild beasts, welcomed Sir Thomas Roe with the same enthusiasm he had shown for the arrival of the first turkey in India, and questioned Roe closely on the distant, foggy island he came from, and the strange things that went on there.

For the committee who planned the House of Commons paintings, this marked the beginning of British engagement with India: two nation states coming into direct contact for the first time.

Yet, in reality, British relations with India began not with diplomacy and the meeting of envoys, but with trade.

On 24 September, 1599, 80 merchants and adventurers met at the Founders Hall in the City of London and agreed to petition Queen Elizabeth I to start up a company.

A year later, the Governor and Company of Merchants trading to the East Indies, a group of 218 men, received a royal charter, giving them a monopoly for 15 years over “trade to the East”.

The charter authorised the setting up of what was then a radical new type of business: not a family partnership – until then the norm over most of the globe – but a joint-stock company that could issue tradeable shares on the open market to any number of investors, a mechanism capable of realising much larger amounts of capital.

The first chartered joint-stock company was the Muscovy Company, which received its charter in 1555. The East India Company was founded 44 years later. No mention was made in the charter of the EIC holding overseas territory, but it did give the company the right “to wage war” where necessary.

Six years before Roe’s expedition, on 28 August 1608, William Hawkins had landed at Surat, the first commander of a company vessel to set foot on Indian soil.

Hawkins, a bibulous sea dog, made his way to Agra, where he accepted a wife offered to him by the emperor, and brought her back to England. This was a version of history the House of Commons hanging committee chose to forget.

The rapid rise of the East India Company was made possible by the catastrophically rapid decline of the Mughals during the 18th century.

As late as 1739, when Clive was only 14 years old, the Mughals still ruled a vast empire that stretched from Kabul to Madras. But in that year, the Persian adventurer Nadir Shah descended the Khyber Pass with 150,000 of his cavalry and defeated a Mughal army of 1.5 million men.

Three months later, Nadir Shah returned to Persia carrying the pick of the treasures the Mughal empire had amassed in its 200 years of conquest: a caravan of riches that included Shah Jahan’s magnificent peacock throne, the Koh-i-Noor, the largest diamond in the world, as well as its “sister”, the Darya Nur, and “700 elephants, 4,000 camels and 12,000 horses carrying wagons all laden with gold, silver and precious stones”, worth an estimated £87.5m in the currency of the time.

This haul was many times more valuable than that later extracted by Clive from the peripheral province of Bengal.

The destruction of Mughal power by Nadir Shah, and his removal of the funds that had financed it, quickly led to the disintegration of the empire.

That same year, the French Compagnie des Indes began minting its own coins, and soon, without anyone to stop them, both the French and the English were drilling their own sepoys and militarising their operations. Before long the EIC was straddling the globe.

Almost single-handedly, it reversed the balance of trade, which from Roman times on had led to a continual drain of western bullion eastwards.

The EIC ferried opium to China, and in due course fought the opium wars in order to seize an offshore base at Hong Kong and safeguard its profitable monopoly in narcotics.

To the west it shipped Chinese tea to Massachusetts, where its dumping in Boston harbour triggered the American war of independence.

By 1803, when the EIC captured the Mughal capital of Delhi, it had trained up a private security force of around 260,000- twice the size of the British army – and marshalled more firepower than any nation state in Asia.

It was “an empire within an empire”, as one of its directors admitted. It had also by this stage created a vast and sophisticated administration and civil service, built much of London’s docklands and come close to generating nearly half of Britain’s trade. No wonder that the EIC now referred to itself as “the grandest society of merchants in the Universe”.

Yet, like more recent mega-corporations, the EIC proved at once hugely powerful and oddly vulnerable to economic uncertainty.

Only seven years after the granting of the Diwani, when the company’s share price had doubled overnight after it acquired the wealth of the treasury of Bengal, the East India bubble burst after plunder and famine in Bengal led to massive shortfalls in expected land revenues.

The EIC was left with debts of £1.5m and a bill of £1m unpaid tax owed to the Crown. When knowledge of this became public, 30 banks collapsed like dominoes across Europe, bringing trade to a standstill.

In a scene that seems horribly familiar to us today, this hyper-aggressive corporation had to come clean and ask for a massive government bailout.

On 15 July 1772, the directors of the East India Company applied to the Bank of England for a loan of £400,000. A fortnight later, they returned, asking for an additional £300,000. The bank raised only £200,000.

By August, the directors were whispering to the government that they would actually need an unprecedented sum of a further £1m. The official report the following year, written by Edmund Burke, foresaw that the EIC’s financial problems could potentially “like a mill-stone, drag [the government] down into an unfathomable abyss … This cursed Company would, at last, like a viper, be the destruction of the country which fostered it at its bosom.”

The East India Company really was too big to fail. So it was that in 1773 it was saved by history’s first mega-bailout

But unlike Lehman Brothers, the East India Company really was too big to fail. So it was that in 1773, the world’s first aggressive multinational corporation was saved by history’s first mega-bailout – the first example of a nation state extracting, as its price for saving a failing corporation, the right to regulate and severely rein it in.

***

In Allahabad, I hired a small dinghy from beneath the fort’s walls and asked the boatman to row me upstream.

It was that beautiful moment, an hour before sunset, that north Indians call godhulibela – cow-dust time – and the Yamuna glittered in the evening light as brightly as any of the gems of Powis.

Egrets picked their way along the banks, past pilgrims taking a dip near the auspicious point of confluence, where the Yamuna meets the Ganges. Ranks of little boys with fishing lines stood among the holy men and the pilgrims, engaged in the less mystical task of trying to hook catfish. Parakeets swooped out of cavities in the battlements, mynahs called to roost.

For 40 minutes we drifted slowly, the water gently lapping against the sides of the boat, past the mile-long succession of mighty towers and projecting bastions of the fort, each decorated with superb Mughal kiosks, lattices and finials.

It seemed impossible that a single London corporation, however ruthless and aggressive, could have conquered an empire that was so magnificently strong, so confident in its own strength and brilliance and effortless sense of beauty.

Historians propose many reasons: the fracturing of Mughal India into tiny, competing states; the military edge that the industrial revolution had given the European powers.

But perhaps most crucial was the support that the East India Company enjoyed from the British parliament. The relationship between them grew steadily more symbiotic throughout the 18th century.

Returned nabobs like Clive used their wealth to buy both MPs and parliamentary seats – the famous Rotten Boroughs. In turn, parliament backed the company with state power: the ships and soldiers that were needed when the French and British East India Companies trained their guns on each other.

As I drifted on past the fort walls, I thought about the nexus between corporations and politicians in India today – which has delivered individual fortunes to rival those amassed by Clive and his fellow company directors.

The country today has 6.9% of the world’s thousand or so billionaires, though its gross domestic product is only 2.1% of world GDP.

The total wealth of India’s billionaires is equivalent to around 10% of the nation’s GDP – while the comparable ratio for China’s billionaires is less than 3%.

More importantly, many of these fortunes have been created by manipulating state power – using political influence to secure rights to land and minerals, “flexibility” in regulation, and protection from foreign competition.

Multinationals still have villainous reputations in India, and with good reason; the many thousands of dead and injured in the Bhopal gas disaster of 1984 cannot be easily forgotten; the gas plant’s owner, the American multinational, Union Carbide, has managed to avoid prosecution or the payment of any meaningful compensation in the 30 years since.

But the biggest Indian corporations, such as Reliance, Tata, DLF and Adani have shown themselves far more skilled than their foreign competitors in influencing Indian policymakers and the media.

Reliance is now India’s biggest media company, as well as its biggest conglomerate; its owner, Mukesh Ambani, has unprecedented political access and power.

The last five years of India’s Congress party government were marked by a succession of corruption scandals that ranged from land and mineral giveaways to the corrupt sale of mobile phone spectrum at a fraction of its value.

The consequent public disgust was the principal reason for the Congress party’s catastrophic defeat in the general election last May, though the country’s crony capitalists are unlikely to suffer as a result.

Estimated to have cost $4.9bn – perhaps the second most expensive ballot in democratic history after the US presidential election in 2012 – it brought Narendra Modi to power on a tidal wave of corporate donations.

Exact figures are hard to come by, but Modi’s Bharatiya Janata party (BJP), is estimated to have spent at least $1bn on print and broadcast advertising alone.

Of these donations, around 90% comes from unlisted corporate sources, given in return for who knows what undeclared promises of access and favours. The sheer strength of Modi’s new government means that those corporate backers may not be able to extract all they had hoped for, but there will certainly be rewards for the money donated.

In September, the governor of India’s central bank, Raghuram Rajan, made a speech in Mumbai expressing his anxieties about corporate money eroding the integrity of parliament: “Even as our democracy and our economy have become more vibrant,” he said, “an important issue in the recent election was whether we had substituted the crony socialism of the past with crony capitalism, where the rich and the influential are alleged to have received land, natural resources and spectrum in return for payoffs to venal politicians. By killing transparency and competition, crony capitalism is harmful to free enterprise, and economic growth. And by substituting special interests for the public interest, it is harmful to democratic expression.”

His anxieties were remarkably like those expressed in Britain more than 200 years earlier, when the East India Company had become synonymous with ostentatious wealth and political corruption: “What is England now?” fumed the Whig litterateur Horace Walpole, “A sink of Indian wealth.”

In 1767 the company bought off parliamentary opposition by donating £400,000 to the Crown in return for its continued right to govern Bengal. But the anger against it finally reached ignition point on 13 February 1788, at the impeachment, for looting and corruption, of Clive’s successor as governor of Bengal, Warren Hastings.

It was the nearest the British ever got to putting the EIC on trial, and they did so with one of their greatest orators at the helm – Edmund Burke.

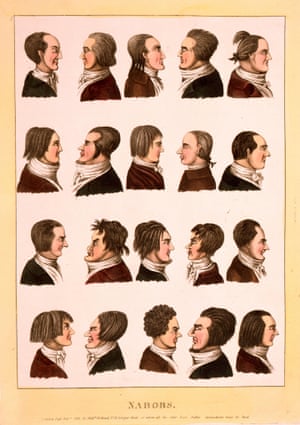

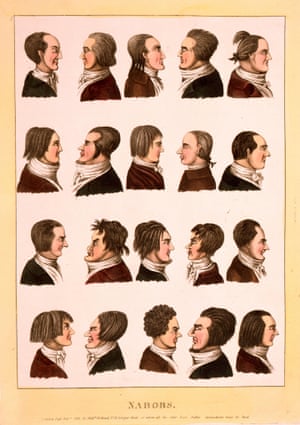

Portraits of Nabobs, or representatives of the East India Company. Photograph: Alamy

Burke, leading the prosecution, railed against the way the returned company “nabobs” (or “nobs”, both corruptions of the Urdu word “Nawab”) were buying parliamentary influence, not just by bribing MPs to vote for their interests, but by corruptly using their Indian plunder to bribe their way into parliamentary office: “To-day the Commons of Great Britain prosecutes the delinquents of India,” thundered Burke, referring to the returned nabobs. “Tomorrow these delinquents of India may be the Commons of Great Britain.”

Burke thus correctly identified what remains today one of the great anxieties of modern liberal democracies: the ability of a ruthless corporation corruptly to buy a legislature.

And just as corporations now recruit retired politicians in order to exploit their establishment contacts and use their influence, so did the East India Company.

So it was, for example, that Lord Cornwallis, the man who oversaw the loss of the American colonies to Washington, was recruited by the EIC to oversee its Indian territories.

As one observer wrote: “Of all human conditions, perhaps the most brilliant and at the same time the most anomalous, is that of the Governor General of British India. A private English gentleman, and the servant of a joint-stock company, during the brief period of his government he is the deputed sovereign of the greatest empire in the world; the ruler of a hundred million men; while dependant kings and princes bow down to him with a deferential awe and submission. There is nothing in history analogous to this position …”

Hastings survived his impeachment, but parliament did finally remove the EIC from power following the great Indian Uprising of 1857, some 90 years after the granting of the Diwani and 60 years after Hastings’s own trial.

On 10 May 1857, the EIC’s own security forces rose up against their employer and on successfully crushing the insurgency, after nine uncertain months, the company distinguished itself for a final time by hanging and murdering tens of thousands of suspected rebels in the bazaar towns that lined the Ganges – probably the most bloody episode in the entire history of British colonialism.

Enough was enough. The same parliament that had done so much to enable the EIC to rise to unprecedented power, finally gobbled up its own baby. The British state, alerted to the dangers posed by corporate greed and incompetence, successfully tamed history’s most voracious corporation.

In 1859, it was again within the walls of Allahabad Fort that the governor general, Lord Canning, formally announced that the company’s Indian possessions would be nationalised and pass into the control of the British Crown. Queen Victoria, rather than the directors of the EIC would henceforth be ruler of India.

The East India Company limped on in its amputated form for another 15 years, finally shutting down in 1874. Its brand name is now owned by a Gujarati businessman who uses it to sell “condiments and fine foods” from a showroom in London’s West End.

Meanwhile, in a nice piece of historical and karmic symmetry, the current occupant of Powis Castle is married to a Bengali woman and photographs of a very Indian wedding were proudly on show in the Powis tearoom. This means that Clive’s descendants and inheritors will be half-Indian.

***

Today we are back to a world that would be familiar to Sir Thomas Roe, where the wealth of the west has begun again to drain eastwards, in the way it did from Roman times until the birth of the East India Company.

When a British prime minister (or French president) visits India, he no longer comes as Clive did, to dictate terms. In fact, negotiation of any kind has passed from the agenda. Like Roe, he comes as a supplicant begging for business, and with him come the CEOs of his country’s biggest corporations.

The idea of the joint-stock company is arguably one of Britain’s most important exports to India

For the corporation – a revolutionary European invention contemporaneous with the beginnings of European colonialism, and which helped give Europe its competitive edge – has continued to thrive long after the collapse of European imperialism.

When historians discuss the legacy of British colonialism in India, they usually mention democracy, the rule of law, railways, tea and cricket.

Yet the idea of the joint-stock company is arguably one of Britain’s most important exports to India, and the one that has for better or worse changed South Asia as much any other European idea.

Its influence certainly outweighs that of communism and Protestant Christianity, and possibly even that of democracy.

Companies and corporations now occupy the time and energy of more Indians than any institution other than the family. This should come as no surprise: as Ira Jackson, the former director of Harvard’s Centre for Business and Government, recently noted, corporations and their leaders have today “displaced politics and politicians as … the new high priests and oligarchs of our system”. Covertly, companies still govern the lives of a significant proportion of the human race.

The 300-year-old question of how to cope with the power and perils of large multinational corporations remains today without a clear answer: it is not clear how a nation state can adequately protect itself and its citizens from corporate excess.

As the international subprime bubble and bank collapses of 2007-2009 have so recently demonstrated, just as corporations can shape the destiny of nations, they can also drag down their economies.

In all, US and European banks lost more than $1tn on toxic assets from January 2007 to September 2009.

What Burke feared the East India Company would do to England in 1772 actually happened to Iceland in 2008-11, when the systemic collapse of all three of the country’s major privately owned commercial banks brought the country to the brink of complete bankruptcy.

A powerful corporation can still overwhelm or subvert a state every bit as effectively as the East India Company did in Bengal in 1765.

Corporate influence, with its fatal mix of power, money and unaccountability, is particularly potent and dangerous in frail states where corporations are insufficiently or ineffectually regulated, and where the purchasing power of a large company can outbid or overwhelm an underfunded government.

This would seem to have been the case under the Congress government that ruled India until last year. Yet as we have seen in London, media organisations can still bend under the influence of corporations such as HSBC – while Sir Malcolm Rifkind’s boast about opening British embassies for the benefit of Chinese firms shows that the nexus between business and politics is as tight as it has ever been.

The East India Company no longer exists, and it has, thankfully, no exact modern equivalent. Walmart, which is the world’s largest corporation in revenue terms, does not number among its assets a fleet of nuclear submarines; neither Facebook nor Shell possesses regiments of infantry.

Yet the East India Company – the first great multinational corporation, and the first to run amok – was the ultimate model for many of today’s joint-stock corporations.

The most powerful among them do not need their own armies: they can rely on governments to protect their interests and bail them out.

The East India Company remains history’s most terrifying warning about the potential for the abuse of corporate power – and the insidious means by which the interests of shareholders become those of the state.

Three hundred and fifteen years after its founding, its story has never been more current.

William Dalrymple’s new book, The Anarchy: How a Corporation Replaced the Mughal Empire, 1756-1803, will be published next year by Bloomsbury & Knopf

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/mar/04/east-india-company-original-corporate-raiders?CMP=share_btn_fb