The 'FAKE' BREAST TAX narrative of commies & evangis

Before year 2000, nobody ever heard of the term 'Breast Tax' . The first mention of this story in a book on social history by an Ezhava writer, S.N Sadasivan, published in 2000, which does not cite any reference.

As is common practice of commies and evangis, something will be written without any evidence and soon others will quote this as the reference and spread it through their networks.

A commie who never contributes anything useful to the society will base his entire life (and livelihood) talking about oppression. He will participate and organize meetings every day and will repeat this daily to every age group. The evangi will do the same in his church group. They will create artwork and slogans and the stories will become bigger. Street plays will be conducted everywhere. New additional stories will be created to strengthen the narrative.

Another commie CK Radhakrishnan in 2007 now writes about "The Unforgettable Contributions of Nangeli in Kerala", where he reveals that "Today, if anyone remembers her sacrifice, it is only vocally transmuted to the next generation. Some of her (Nangeli's) relatives have only vague memories of her and that too is becoming thinned in the passage of generations and time. Only Leela (61) belonging to the fourth generation of Nangeli has kept alive the memories her courageous ancestor".

Now, we all must now rely only on the family recollections of one old lady for this gory and poetic account.

But all diligent colonial historians, missionaries and record keepers of Travancore mysteriously missed this important event.

By late 2013, the story is taken up by the national dailies, 200 years on, Nangeli’s sacrifice will have obligatory observations about the struggle against a Brahmanic patriarchy. An unknown Nangeli will even be assigned a day to honor her contributions.

The only group who covered their breasts in Kerala were those who belong to Muslim, Jew and Christian faith. Muslim ladies worn a long loose jacket called Kuppayam (Jacket in Malayalam) while Christian ladies worn a tighter version of it, called Chatta.

It was common practice in Kerala, Tamil Nādu and in fact in most parts of India till the prudish white man came with his 'christian' values.

Ibn Batuta (died 1369), the north African Islamic traveller, had given detailed accounts of the girls exposing their breasts in public in Kerala. When he was anointed as the Mullah at the new mosque in Maldives, by Calicut King Zamorin, Ibn Batuta tried to make the young Muslim women cover up their breasts and wear purdah, and he fell into heavy opposition-for as per local custom this "bouncing bare breasts in public” was just normal culture.

He was then ordered by Zamorin to stop his nonsense, and not to create disharmony–and then he left for Sri Lanka.

‘Mulakkaram’ …not ‘Mulakkam’. It wasn’t a tax on ‘breasts’ but a tax per female referred to by the female part of the anatomy because it was lower for women. The corresponding higher tax on men was ‘Thalakkaram’. Thala = head. Mula = breast. Mula was used to rhyme with Thala.

The Travancore rulers had got the help of British to ward off their threats and in the disguise of protection the British were successful in gaining the trust of the rulers. They had influence in the higher echelons of Madambis, or local chieftains, and they began exerting their power on the kingdom by appointing their own Regent Col. Munroe.

The kingdom had to pay a protectorate fee towards the British for their services. For this the kingdom had to implement both Mulakkaram and Thalakkaram - basically 'Woman tax' and 'Man tax'.

The landlords were supposed to pay these taxes according to the number of laborers they had in their service. If there were 10 women laborers they paid 10 Mulakkaram and for 10 men they paid 10 Thalakkaram.

The tax amount on Women was lower than Men. To make this distinction, the term Mulakkaram was used to denote the Women's tax and Thalakkaram was used to denote the tax due from men.

Problems arose when the British Regent exempted the converted Christians from these taxes. There was an upraising in the Channar community against the exemptions given for converted Christians in both upper cloth and taxes. This revolt became the Channar Revolt or the Marumarakkal Samaram, as told in Malayalam, or the Thol Seelai Kalaham, as told in Tamil. After this revolt the taxes were almost stopped altogether. And there ends the story of Breast Tax.

The poll tax was levied on every adult i.e. 14yo present in the kingdom, and it was called Thalakkaram (head tax) for the men & Mulakkaram (breast tax) for the women. Although the tax was nominal (atleast according to the officials collecting them) it was very burdensome to the local populace when combined with other taxes. It was abolished in the year 1040 of the Malayalam Era (Around 1864-65 CE) along with 110 other such taxes

[Sources :-

Travancore Tribes & Caste (1937) by LA Krishna Iyer

Native life in Travancore (1885) by Rev Samuel Mateer]

Other references from History

The next foreign traveller who mentions this practice is Marco Polo who mentions

You must know that in all this Province of Maabar there is never a Tailor to cut a coat or stitch it, seeing that everybody goes naked! For decency only do they wear a scrap of cloth; and so 'tis with men and women, with rich and poor, aye, and with the King himself, except what I am going to mention.

It is a fact that the King goes as bare as the rest, only round his loins he has a piece of fine cloth, and round his neck he has a necklace entirely of precious stones,--rubies, sapphires, emeralds, and the like, insomuch that this collar is of great value

Then in the 18th century John Grose in his Voyage to East Indies & James Forbes in his Oriental Memoirs mention that women in Kerala didn't cover upper part of their bodies.

So from the available evidence women not covering their upper bodies seem to be an universal practice in Kerala, so much so that when Raja Ravi Verma painted a portrait of the queen of Travancore the queen posed with a thin strip of cloth barely covering her chest. LA Krishna Iyer again mentions in his other work Cochin Tribes & Castes (page 100). {This work contains many pictures of Nambudiri Brahmin women themselves going around topless, including a curious picture of a Nambudri lady & a bride, where the bride is the only one who has covered her upper body}

The absence of any covering for the bosom in ordinary female dress has drawn much ridicule on the Nayars, and this custom has been much misunderstood by foreigners. So far from indicating immodesty, it is looked upon by the people themselves in exactly the opposite light…”A custom has in it nothing indecent when it is universal,”

The problem in this case arises from the attempt to apply our modern concepts of modesty to historical practices. How wrong this approach could be is best illustrated by a curious incident mentioned by C Kesavan, who was the first elected chief minister of Travancore, in his autobiography Jeevitha Samaram. He mentions that one of his sister-in-laws procured a blouse & went around wearing it, showing it to ladies of the village only to find her mother standing with a coconut branch to beat her with for "roaming shamelessly wearing shirts like the Muslim women" [sic]

These attitudes started changing with the arrival of Xtian missionaries in Kerala, who asked the new converts to cover themselves for the sake of decency leading to the famous cloth struggles of the 19th century.

It was fairly common even for this generation to have seen our grandmothers without blouses.

The power of propaganda

Repeat a lie long enough over time people are bound to believe it to be the reality. Breast Tax was mentioned in a communist play the very first time and it's fiction but now it's even parroted in Western University books and believed faithfully by the newer generations. This is how fictional history is created by the west and commies.

Mulakkaram is a communist construct without basis, but on a concocted story. They (commies) even these days trumpet this false notion to nurture the working class allegiance. Misfortune of Kerala to suffer ignominy without any alternative in sight!

All men and women irrespective of caste in the subcontinent went topless for thousands of years till the Islamic and later the Victorian era came. Both words - blouse and petticoat- are of British origin. There existed no such words or clothes in India. All adults wore Two unstitched single piece garments.

The bottom was wrapped around waist and then tucked from under the legs (adults only) to form a pant like thing. The smaller cloth piece was just dropped like dupatta for women. Or tied in waist. Or wrapped like shawl. Depending on weather. No one minded seeing open breasts.

There is recorded history of Queens from Kerala not wearing upper cloth.

Dutch representative William Van Nieuhoff in the 17th century writes about the attire of Ashwathi Thirunal Umayamma Rani, then queen of Travancore:“… I was introduced into her majesty’s presence. She had a guard of above 700 Nair soldiers about her, all clad after the Malabar fashion; the Queens attire being no more than a piece of callicoe wrapt around her middle, the upper part of her body appearing for the most part naked, with a piece of callicoe hanging carelessly round her shoulders.”

Now let's look at how a Brahmin upper class lady would usually dress. Mind you the one on the right is a bride.

Also look at the following images were Nair, one ring below the Brahmins, ladies are shown wearing their best on festive occasions.

You can see that these women are either scantily clothed or wearing nothing above their waistline. So the argument that whether these women were allowed to wear upper clothes or not is based totally on whether they could afford it or not.

To argue this point let us look at the pictures of some well-off Ezhavas, another rung below the Nair, families.

You can see that they are all wearing upper clothes. Hence the custom in Kerala was to not wear much of upper clothes. The same is true for both men and women. Only Muslim ladies used to wear an upper cloth in those areas and later with the help of British regent, Christian converts in the Nadar or Channar castes were allowed to wear the upper cloth.

Surprising to see sudden spurt in a story being pushed as an EVIL collectively by several people. Books are being written on a fake story as is standard commie/evangi operating procedure.

With conversion to Christianity by some, they got some recognition and social status. With start of NEW Tea plantation in Ceylon and Sugar factories, Nadar's started to earn and save some money to afford 'CLOTH' a luxury. Some turned land owners and few tree owners.

A decree from Synod allowed converted christianity to follow untouchability while it was punishable in rest of the world. (Divide with convenience?) Surprisingly, converted unprivileged to Christianity still follow caste system.

During the period British gaining power, Col Munro in 1812 and 1814 Govt of Trav. permitted some clothing to the converted unprivileged not same as syrian christians & moplahs. (UNFAIR & divisive) This triggered the UPPER CLOTH MOVEMENT

The Nadar's unrest got further momentum when seasonal migrant Thirunelveli Nadar covering upper body have to bare in Trivancore. The Upper cloth movement can be categorised in 3 phases

While some rich NADAR wore upper clothes and poorer not, A DIVIDE was created not on CASTE lines but Poor and Riches Finally, a Royal Proclamation was issued on 26,July 1859, abolishing all restrictions on covering upper parts by Shanar woman except not to imitate high class

—-------

The recurring myth of breast tax doesn't seem to die down, this time propagated by 'Scroll'

There are many allowances we can make for a false story published by a media outlet should we choose to give the benefit of the doubt, ranging from human error to acknowledging the volume of unverified or unverifiable information floating in the web with vague references that seem genuine. But when a story reappears over and over in the media, even after it has been busted as nothing but fantasy, it is pertinent to question the motive.

The vicious story of ‘breast tax’ that

scroll.in published recently, is one such modern fabrication that keeps appearing in the media repeatedly – a graphic story about a supposed ‘breast tax’ in practice in 19th Century Kerala.

The story

This imaginative story claims that upper caste Nairs and Nambuthiri Brahmins in Kerala did not allow women from lower castes to cover their breasts and then levied ‘breast tax’ on them. In such an exploitative society, the story goes, rose Nangeli, an Ezhava woman who protested the unfair tax system by chopping her breasts off, attaining martyrdom.

Of the many instances of atrocities in history, this may well be one of the most violent and graphic. Shaming of lower castes and what’s more, outrage of women’s modesty as a tool of oppression is surely the worst kind of exploitation one can imagine. Even as we read the story, the picture floats easily into our mind’s view: richly attired noblemen and ladies seated smugly on their ornate cushions, giving an outrageous decree, while dark and lanky, slavish people dressed in rags, bowing almost to the ground, listen but barely showing emotion. Only, we need to pause the imagination for a while to step back and ask a necessary question: just because a story is vivid and graphic in its imagery, does it become fact?

Kerala’s sartorial history

Let’s begin with a primer on the attire of women in 19th century Kerala, before we address the lack of authenticity of the story, the mindset, motives and motivations behind such a fabrication.

Kerala’s world famous tropical climate needs no introduction. Also, a widely observed pattern is that the traditional attire of a people is directly dependent on the climate of the land. Owing to the humid heat all through the year, a piece of cotton cloth draped around the middle with another (optional) hung over the shoulder as an afterthought, has largely been the traditional attire of the people of Kerala, regardless of gender or caste.

A 17th-Century Dutch visitor William Van Nieuhoff writes about the attire of Ashwathi Thirunal Umayamma Rani, then queen of Travancore, in the following manner:

“… I was introduced into her majesty’s presence. She had a guard of above 700 Nair soldiers about her, all clad after the Malabar fashion; the Queen’s attire being no more than a piece of callicoe wrapt around her middle, the upper part of her body appearing for the most part naked, with a piece of callicoe hanging carelessly round her shoulders.”

He drew a sketch of the queen and her attendants in his work (Voyages and travels to the East Indies; 1653-1670), where it is quite clear that the queen and her attendants wore little to no cloth to cover their bosoms.

Johan Nieuhoff meeting the Queen of Travancore. (Source: here)

If 17th Century seems a bit dated for our debate, let’s look at a few evidences from 19th and early 20th centuries, the very era our fable is supposed to have taken place. The story implies that nakedness was a humiliation imposed by the upper caste on the lower caste women, with the intention of depriving them of modesty and the luxury of wearing a second piece of cloth. This accusation hardly holds water when you realise that women of Nambuthiri families and affluent Nair families themselves saw no need for a breast-covering garment, either as a sign of luxury or ‘modesty’.

A Nambuthiri Brahmin woman from a 20th century Malayalam book by Kanippayyur Shankaran

Namboodiripad

Nambuthiri Brahmin women , from ‘The Cochin Tribes and Castes’ by L. K. Anantha Krishna Iyer -Nair girls and men in a temple procession, from the book by L. K. Anantha Krishna Iyer

Nair girls from the book by L. K. Anantha Krishna Iyer

‘Modesty’ (?) in Art

While the images above are photographs of upper caste women from the era, the ones that follow are paintings of women of royalty, by the celebrated painter Raja Ravi Varma.

A 19th Century painting of Junior Rani of Travancore, Bharani Thirunal Rani Parvathi Bayi by Raja Ravi Varma (Source: here)

A 19th Century painting, ‘Malabar Beauty’ by Raja Ravi Varma (Source: here)

A connoisseur of portraiture would note the elegant pose of the women, who, guided by the artist surely, took care to hold the unstitched cloth in place as a mere accessory, in a manner that the ornaments on the left hand and the neck could be highlighted, and compare it to how a modern-day woman might hold up her exquisite handbag with one hand, the other hand on the waist, accentuating her lithe form and highlighting her classy taste in accessories, while smiling at the camera.

L.K. Anantha Krishna Iyer in his book, The Cochin Tribes and Castes (pg. 100) writes the following about the clothing of upper caste Nair women during early 20th century:

The absence of any covering for the bosom in ordinary female dress has drawn much ridicule on the Nayars, and this custom has been much misunderstood by foreigners. So far from indicating immodesty, it is looked upon by the people themselves in exactly the opposite light…”A custom has in it nothing indecent when it is universal,” as one of the travellers philosophically remarks (Dall).

In the 20th century however, with the advent of modern (and Western, through colonial intervention) sensibilities of fashion and propriety, people of all backgrounds started to wear a stitched upper garment, or tuck in an unstitched cloth around the chest to form a full-bodied attire.

Ezhava girls, from the book by L. K. Anantha Krishna Iyer

Ezhava family from an early 20th century book titled ‘Glimpses of Travancore’ by N. K. Venkateswaran

Through all these records and more, it is fairly evident that the sartorial practices in Kerala changed organically with time, a phenomenon that is observed uniformly across the world.

Who was Nangeli?

As to the specific story of Nangeli and her self-mutilation as protest, there are no historical records of any authenticity of such an event taking place.

A careful look at the references and sources of the Wikipedia article on

Nangeli reveal that all of them are from the last decade and mostly from the last couple of years. None of them cites any historical records on Nangeli.

Where did the story come from?

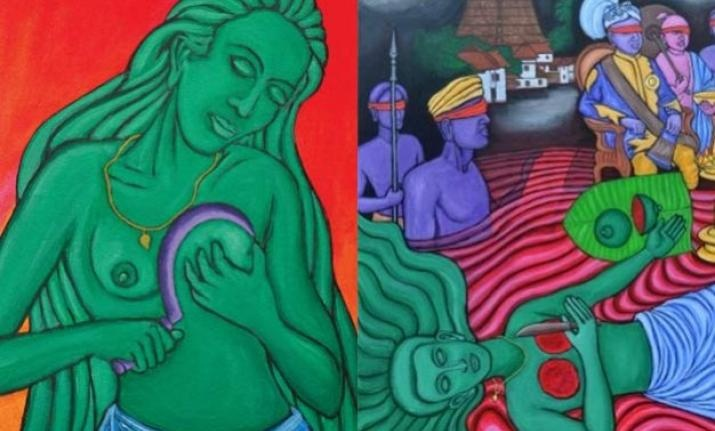

The mysteriously new Nangeli story was recently popularized by a Malayali painter named T Murali who refers to himself as Chitrakaran. Interestingly, Chitrakaran’s blog is quite a fascinating study of his extremely bitter and hateful mindset towards Hindu deities and culture. For example, in this

blogpost he ‘muses’ about Devi Saraswati in a crass manner that speaks volumes about his

blind hatred rather than any intellectual authenticity.

He says:

“സമൂഹത്തിലെഭക്തിഭ്രാന്ത്കൂടിവരുന്നസാഹചര്യത്തില്സരസ്വതിയുടെമുലകളുടെമുഴുപ്പ്, സരസ്വതിഉപയോഗിക്കുന്നസാരി, ബ്രായുടെബ്രാന്ഡ്തനെയിം, പാന്റീസ്, തുടങ്ങിയവസ്തുതകളെക്കുറിച്ച്ചിന്തിക്കുന്നത്പ്രസക്തമാണെന്ന്ബോധോദയമുണ്ടായിരിക്കുന്നു.”

Translation:

“Since bhakti (he calls it ‘madness’) towards Gods is becoming popular in the society, thought that it is relevant to think about the breast size of Sarasvati, the brand name of bra and panties which she uses etc.”

Another statement from the blog :

“ബ്രാഹ്മണന്റെമഹാവിഷ്ണുഎന്നകുണ്ടന്ദൈവത്തിന്(മോഹിനിയാട്ടക്കാരി/രന്)എത്രലിംഗമുണ്ടെന്നും,എത്രയോനിയുണ്ടെന്നുംചിത്രകാരന്സന്ദേഹിച്ചുകൊണ്ടിരിക്കുന്നസത്യംകൂടിവെളിപ്പെടുത്തട്ടെ”

Translation:

“Let me also reveal that Chitrakaran (addressing himself) has been thinking about how many penises and vaginas the gay God Vishnu of Brahmins has.”

Making rude, incoherent allusions to genitals with an intent to vilify simply because devotion is becoming popular, by the blogger’s own admission, is an unwarranted expression of hatred towards a certain culture and an extreme example of unapologetic bigotry.

The fact, then, that a person with known hatred for Hindu culture, a propensity for vivid, graphic imagination and a tendency for irreverent sexualisation popularises a fictional story about non-existent ‘breast tax’ is quite telling.

Forget the messenger, what about the message?

Having discussed the true nature of Kerala’s cultural history, it would be naïve to take a stance that any accusation of social exploitation is false. Any astute observer of social psychology would readily admit that oppression, discrimination and exploitation have existed in all societies in one form or the other in varying degrees in every era, including the current one.

Kerala, like all other regions of the world, has had its share of social inequalities and injustice as a consequence. The exemplary life and work of Sri Narayana Guru (born into an Ezhava family and faced much discrimination) in the area of social reform stand as testimony to the issues that troubled the society in the 19th Century. The study into historical evidences so far is not to deny the issue of exploitation altogether, but to explore a much deeper question: when Kerala’s history offers quite a few incidents and stories about social discrimination, why does a certain section of the media feel the need to fabricate a new story that has no basis in truth? Why can’t we talk about real issues with real basis in history, with genuine care and introspection, rather than throw outrageously wild allegations that are completely in contradiction with reality?

What purpose does Nangeli’s story serve?

Clearly, now that we have established it as fiction, Nangeli’s story is a strong concoction of all the ingredients that are accepted as most despicable in a civilised society. Humiliation of women, oppression of a community, tyranny of unfair tax – all of these hint to a cruel, oppressive regime and a society with a morally corrupt core.

In short, we are presented with a black-and-white image of an oppressive rule (of the Travancore and Cochin Kings) and victimised subjects that validates intense hatred, irrational anger towards ruling-class “oppressors” and makes the present-day problems pale in comparison to the “dark past”.

Interestingly, the blame of all the terror and oppression, with a story like this, is placed entirely on the upper castes within Kerala society, with hardly a glance at the destructive influence of Colonialism.

A pragmatic approach, one must note, as there is not much political mileage to be achieved by hating European colonisers, and much to be gained by dividing present-day society into blaming each other for past wrongs. With a story like Nangeli’s to sufficiently horrify the modern audience, present-day Kerala with its high Human Development Index and a few inevitable snags here and there, sounds like a liberated haven that has been rescued from its horrendous tyrants.

If this is true, then the world’s sociologists must be writing paeans about this turnaround ‘success story’ in the shortest span known to history. However, a fair, unbiased study of history points us to the efforts of Sethu Lakshmi Bayi, queen of Travancore, who spent nearly a fifth of her revenue on education, contributing to Kerala’s march towards the high literacy rate which we see today. No less is the contribution of Chithira Thirunal, the last Maharaja of Travancore who ended discrimination and permitted entry of people of all castes into upper-caste-owned temples.

So, it appears, that certain sections of the media will resort to any sensationalised, vulgar hype to elicit strong reactions from the audience and impose a skewed worldview that gives strength to one faction of the political propaganda machinery. The world, as much as we want, does not render itself into a black-and-white picture. History and truth are all shades of hues.

Does the story of an Ezhava woman hacking off her breast, has any basis in history?

This part is the most repeated of the story repeated by everyone who believes the story to be true. Unfortunately, all the references to the story are from 10 years and could be attributed to one person, a painter Murali T. whose nom de plume is Chitrakaran. Unfortunately, nobody ever bothers to cross check the story. Because according to Murali's own admission even the supposed kin of Nangeli don't know anything about her

So where this story comes from? The answer again could be found from contemporary sources such as LA Krishna's 1937 work. On page 165 of this book he mentions anapocryphal tale i.e.

Once, when the agent of the Raja went to recover talakaram, the Malayarayan pleaded inability to pay the amount, but the agent insisted on payment. The Arayans were so enraged that they cut off the head of the man and placed it before the Agent saying ‘here is your ‘thalakaram.’ Similarly, inability was pleaded in the case of an Arayan woman from payment of mulakaram, but the Agent again persisted. One breast of the woman was cut off and placed before him saying ‘here is your mulakaram.’ On hearing this incident, the Raja was so enraged at the indiscretion of the agent that he forthwith ordered the discontinuance of this system of receiving payment.

But the unfortunate souls mentioned in this incident are Arayans who were outside the ambit of caste & were as disconnected from the wider caste struggle as possible.

So

The mulakaram existed but it was a poll tax & had nothing to do with the right to cover one's upper body

Women in Kerala up until the early 20th century didn't put much importance to covering the upper body, regardless of caste, a situation which started changing with the arrival of Xtian missionaries in early 19th century, leading to a decades long conflict.